Transformer lifetime cost is a critical factor in the economic performance of power system projects, yet it is often underestimated during the procurement stage. Engineers often compare transformers based on initial purchase price, but this approach overlooks the long-term financial impact of continuous energy losses over decades of operation. For EPC contractors and utilities, conducting a proper transformer lifetime cost analysis helps identify transformer designs that minimize long-term operating expenses rather than focusing only on initial purchase price.

In reality, transformer losses translate directly into operating expenditure, making transformer lifetime cost a far more accurate indicator of total project cost than upfront capital investment alone. As electricity prices rise and efficiency standards tighten, understanding how transformer losses affect lifetime cost has become essential for EPC contractors, utilities, and asset owners seeking sustainable, cost-effective power infrastructure.

Table of Contents

- Introduction: Why Transformer Lifetime Cost Matters

- Understanding Transformer Losses and Cost Structure

- How Transformer Losses Translate into Lifetime Cost

- Electricity Price, Load Profile, and Sensitivity Analysis

- Transformer Loss Standards and Evaluation Methods (IEC vs IEEE)

- How to Optimize Transformer Lifetime Cost During Selection

- Case Study: Lifetime Cost Comparison of Two Transformers

- Common Mistakes in Transformer Lifetime Cost Evaluation

- Conclusion: Transformer Lifetime Cost Decision Checklist

1. Introduction: Why Transformer Lifetime Cost Matters

In power system projects, transformers are often evaluated primarily based on initial purchase price. This approach appears reasonable during procurement, where capital expenditure is visible, measurable, and immediately comparable across competing bids. Procurement teams can easily compare nameplate ratings, delivery schedules, and upfront prices, making capital cost the most intuitive decision metric.

However, for assets designed to operate continuously for 20 to 30 years, the initial purchase price represents only a fraction of the total cost incurred over the transformer’s operational life. Once installed and energized, a transformer begins consuming energy continuously through internal losses. These losses are unavoidable, irreversible, and locked into the system for decades.

Why Lowest Bid Transformers Often Cost More Over Time

Transformer losses generate continuous energy consumption throughout the service life. Unlike maintenance costs, which may vary year by year, loss-related energy consumption occurs every hour the transformer remains energized. These losses convert directly into operating expenditure, which in many projects exceeds the original equipment cost multiple times over.

As electricity prices rise globally and efficiency regulations tighten, transformer lifetime cost has become a decisive factor in project economics rather than a secondary technical consideration. Utilities, EPC contractors, industrial owners, and renewable energy developers increasingly recognize that a transformer is not merely a purchased product, but a long-term energy-consuming asset.

Transformer lifetime cost refers to the total cost incurred over the entire operational life of a transformer, including:

- Initial purchase cost

- Energy cost caused by no-load and load losses

- Auxiliary power consumption from cooling and control systems

- Maintenance, reliability, and operational impacts

Projects that ignore lifetime cost frequently select transformers that appear economical at the procurement stage but impose higher long-term financial burdens through sustained energy losses. In contrast, projects that evaluate losses systematically often achieve lower total owning cost, improved system efficiency, and stronger long-term financial performance.

This article explains how transformer losses affect project lifetime cost, how to evaluate them correctly using engineering-based calculations, and how EPC contractors and asset owners can optimize transformer selection through lifecycle-oriented decision-making.

2. Understanding Transformer Losses and Cost Structure

Transformer losses represent the continuous conversion of electrical energy into heat within the transformer core, windings, and auxiliary systems. These losses are inherent to transformer operation and cannot be eliminated entirely. However, their magnitude varies significantly depending on transformer design, materials, manufacturing quality, operating conditions, and cooling configuration.

From a lifetime cost perspective, understanding the nature of each loss component is essential. Different loss types behave differently over time, respond differently to loading conditions, and contribute unequally to long-term energy cost.

2.1 No-Load Loss and Its Long-Term Impact

No-load loss, also referred to as core loss or iron loss, occurs whenever the transformer is energized, regardless of whether it is supplying load. It originates primarily from hysteresis and eddy current losses in the magnetic core. According to the IEC 60076 standard, no-load loss is measured at rated voltage and frequency and represents a continuous energy consumption component throughout the transformer’s service life.

No-load loss depends mainly on:

- Core material properties

- Magnetic flux density

- Core geometry and lamination structure

- Manufacturing precision and quality control

Because no-load loss is independent of load, it operates continuously as long as the transformer remains energized. In most power systems, transformers are energized 24 hours a day, 365 days a year, even when load demand is low.

For this reason, engineers convert no-load loss power into annual energy consumption using a simple but critical relationship. Annual no-load energy loss is calculated by multiplying no-load loss power by the total operating hours per year:

Eno−load=P0×8760

Where:

- Eno−load is the annual no-load energy loss (kWh/year)

- P0 is the no-load loss power (kW)

- 8760 represents the number of hours in one year

This calculation highlights an important insight: even a small difference in no-load loss, such as 100 W or 200 W, accumulates into thousands of kilowatt-hours over a single year and hundreds of megawatt-hours over a typical 25-year service life.

For distribution transformers, grid-connected substations, and renewable integration points that remain energized continuously, no-load loss often dominates lifetime energy cost. As a result, core material selection and magnetic design play a disproportionately large role in determining transformer lifetime cost.

2.2 Load Loss and Operating Conditions

Load loss, commonly referred to as copper loss or winding loss, results from resistive heating in transformer windings and current-carrying components. Unlike no-load loss, load loss depends directly on the current flowing through the transformer.

From electrical theory, resistive losses increase with the square of current. This means that as transformer loading increases, load loss rises nonlinearly. A transformer operating at 80% load does not experience 80% of rated load loss—it experiences approximately 64% of rated load loss, while operation at full load results in 100% of rated load loss.

Load loss depends on several design and operational factors, including:

- Winding material (copper or aluminum)

- Conductor cross-sectional area

- Winding geometry and joint design

- Operating temperature and cooling effectiveness

To reflect real operating conditions, engineers calculate annual load energy loss using the average load factor. The relationship is expressed as:

Eload=Pk×LF2×8760

Where:

- Eload is the annual load energy loss (kWh/year)

- Pk is the rated load loss at nominal current (kW)

- LF is the average load factor

This squared relationship explains why transformers operating at high utilization experience disproportionately higher lifetime energy costs. In industrial plants, data centers, mining operations, and renewable energy projects with sustained high load factors, load loss often becomes the dominant contributor to transformer lifetime cost.

In high-load applications such as data centers and manufacturing plants, copper winding transformers are often selected to reduce load loss and control long-term operating cost.

2.3 Auxiliary and Cooling Losses

Auxiliary losses originate from cooling systems such as fans, oil pumps, and control equipment. While these losses are typically smaller than core or winding losses, they are often underestimated or excluded during early evaluation.

Auxiliary losses depend on:

- Cooling method (natural or forced)

- Operating temperature

- Load variability

- Environmental conditions

From an energy accounting perspective, auxiliary losses contribute directly to total annual energy consumption. Their annual energy impact is calculated as:

Eaux=Paux×toperation

Where Paux represents auxiliary power demand and toperationt represents the annual operating time of cooling equipment.

In forced-cooled transformers operating under high ambient temperatures or heavy loading, auxiliary losses can become a meaningful component of lifetime cost, particularly over long service periods.

3. How Transformer Losses Translate into Lifetime Cost

Transformer losses affect lifetime cost through continuous energy consumption over decades. Converting technical loss values expressed in kilowatts into financial impact requires several operational assumptions, including operating hours, load profile, electricity price, and service life.

Total annual energy loss is calculated by summing all loss components:

Eannual=Eno−load+Eload+Eaux

Once annual energy loss is known, engineers convert energy consumption into annual cost by applying the local electricity price:

Cannual=Eannual×Ce

Where Ce is the electricity price in USD per kilowatt-hour.

Lifetime loss cost is then calculated by extending annual cost over the transformer’s expected service life:

Clifetime=Cannual×N

Where N represents the service life in years, typically between 20 and 30 years.

Because losses accumulate continuously, small differences in efficiency result in large cumulative financial impacts. A transformer with slightly higher losses may appear competitive at purchase but impose significantly higher operating cost over its lifetime.

Integrating loss calculations into the transformer selection process allows project teams to compare designs based on lifetime cost rather than initial price alone.

This relationship explains why lifetime cost evaluation frequently reverses procurement decisions based solely on initial price.

4. Electricity Price, Load Profile, and Sensitivity Analysis

Transformer losses themselves are defined by physical design and operating conditions, but their economic impact is highly sensitive to external variables. Among these, electricity price and load profile are the two most influential factors shaping transformer lifetime cost.

Ignoring these variables often leads to underestimating long-term operating expense and misjudging the true value of low-loss designs.

4.1 Typical Load Profile Scenarios

Transformers rarely operate at rated load continuously. Instead, they experience fluctuating load patterns determined by the nature of the connected system. Understanding realistic load profiles is essential for accurate lifetime cost evaluation.

In practice, load profiles can be grouped into several representative categories:

| Load Scenario | Typical Load Factor | Common Applications |

|---|---|---|

| Light load | 0.3–0.4 | Rural distribution, standby substations |

| Medium load | 0.5–0.6 | Commercial buildings, mixed-use facilities |

| High load | 0.7–0.85 | Industrial plants, data centers |

Publicly available electricity price data shows that regions with higher tariffs experience disproportionately higher transformer lifetime cost caused by continuous losses.

Because load loss increases with the square of load current, its contribution to lifetime cost rises sharply as load factor increases. This nonlinear behavior explains why a transformer design that performs acceptably under light load conditions may become economically inefficient under sustained high utilization.

From a calculation perspective, this behavior is already embedded in the load loss energy formula:

Eload=Pk×LF2×8760

A change in load factor from 0.5 to 0.75 does not increase load loss by 50%, but by more than 125%. Over a 25-year service life, this difference translates into a substantial operating cost gap.

For EPC contractors and industrial owners, this means that design assumptions about future loading are as important as the transformer’s nameplate efficiency.

4.2 Impact of Electricity Price Variation

Electricity price directly scales transformer lifetime cost. While transformer losses remain physically constant, the monetary value of lost energy changes with tariff levels.

Annual loss cost is calculated as:

Cannual=Eannual×Ce

This linear relationship means that any increase in electricity price immediately and proportionally increases lifetime loss cost.

The table below illustrates the relative impact of electricity price variation on lifetime loss cost:

| Electricity Price (USD/kWh) | Relative Lifetime Loss Cost |

|---|---|

| 0.08 | Baseline |

| 0.12 | +50% |

| 0.18 | +125% |

In regions with high electricity tariffs—such as parts of Europe, Japan, or islanded power systems—loss-related operating cost often exceeds capital cost within the first half of the transformer’s service life.

Even in regions with currently low electricity prices, long-term projects must consider price escalation risk. Over a 25–30 year horizon, modest annual increases in electricity price significantly amplify the economic importance of loss optimization.

4.3 Combined Sensitivity Analysis: Load and Price

The combined effect of load factor and electricity price defines the true financial risk exposure associated with transformer losses.

From a simplified perspective, lifetime cost sensitivity can be expressed as:

Clifetime∝(P0+Pk×LF2)×Ce

This expression highlights three critical insights:

- No-load loss contributes continuously, regardless of loading

- Load loss accelerates rapidly as utilization increases

- Electricity price magnifies all loss components equally

When high load factors coincide with high electricity prices, transformer lifetime cost escalates rapidly. This scenario is common in industrial plants, data centers, and renewable energy hubs located in high-tariff regions.

Sensitivity analysis allows project teams to test multiple scenarios and identify break-even points where higher-efficiency transformers become economically justified. In many cases, sensitivity analysis demonstrates that investing in lower-loss designs reduces total project risk rather than increasing cost.

5. Transformer Loss Standards and Evaluation Methods (IEC vs IEEE)

Accurate transformer lifetime cost evaluation requires consistent loss definitions and standardized test methods. Without standardized frameworks, loss values cannot be reliably compared across manufacturers or projects.

Two major international standards dominate transformer loss evaluation: IEC and IEEE.

5.1 IEC Loss Evaluation Approach

IEC standards, particularly IEC 60076, define how transformer losses are measured, reported, and guaranteed.

Under IEC methodology, losses are classified into:

- Perte de chargement

- Perte de chargement

- Auxiliary loss (where applicable)

IEC focuses on technical measurement consistency. Loss values are measured under defined test conditions, allowing fair comparison between transformer designs.

While IEC does not prescribe a specific economic evaluation method, its standardized loss definitions form a reliable technical foundation for lifetime cost analysis. Most international projects rely on IEC loss data as input for project-specific economic models.

5.2 IEEE Loss Evaluation and Total Owning Cost (TOC)

IEEE standards, notably IEEE C57, go a step further by explicitly integrating economic evaluation into procurement decisions.

IEEE introduces the concept of Total Owning Cost (TOC), which combines:

- Initial purchase price

- Capitalized value of no-load losses

- Capitalized value of load losses

The simplified TOC equation is expressed as:

TOC=Purchase Price+(A×P0)+(B×Pk)

Where:

- A and B are loss capitalization factors

- P0 and Pk are no-load and load losses

Loss capitalization factors convert loss power (kW) into present-value monetary cost based on electricity price, service life, and discount rate.

This approach encourages manufacturers to optimize transformer designs toward minimum lifetime cost, rather than minimum purchase price.

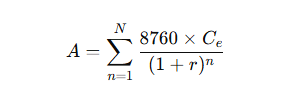

5.3 Loss Capitalization Principles

Loss capitalization translates continuous energy loss into an equivalent upfront cost. The principle is straightforward: a loss that consumes energy every year has a present value that can be compared directly to capital expenditure.

In simplified form, the capitalization factor for no-load loss can be expressed as:

Where:

- N is service life (years)

- Ce is electricity price

- r is discount rate

A similar expression applies for load loss, adjusted for average load factor.

Although full discounted cash flow analysis provides the highest accuracy, many projects apply simplified capitalization factors for practical procurement evaluation. The key requirement is internal consistency—all bids must be evaluated using the same assumptions.

5.4 IEC vs IEEE: Practical Implications for Projects

While IEC and IEEE differ in structure and emphasis, both frameworks support rational lifetime cost evaluation when applied correctly.

- IEC provides technical clarity and comparability

- IEEE provides direct economic decision tools

Problems arise when projects mix IEC loss definitions with IEEE capitalization factors inconsistently. This leads to distorted comparisons and unreliable procurement outcomes.

Successful projects clearly define which standard governs loss measurement and which economic model governs evaluation—before bids are submitted.

6. How to Optimize Transformer Lifetime Cost During Selection

Transformer lifetime cost optimization does not start with loss calculation—it starts with correct selection logic. Many projects fail not because the transformer design is inefficient, but because decision criteria are incomplete or misaligned with real operating conditions.

Effective optimization focuses on balancing technical performance, economic impact, and long-term operational certainty.

6.1 Start With the Operating Reality, Not the Nameplate

One of the most common mistakes in transformer procurement is assuming that rated power reflects actual operating conditions.

In reality, the following parameters matter far more than nameplate capacity:

| Paramètre | Why It Matters |

|---|---|

| Average load factor | Determines real load loss contribution |

| Load growth expectation | Impacts future loss escalation |

| Duty cycle | Influences thermal aging and efficiency |

| Ambient temperature | Affects cooling efficiency |

For example, a transformer operating at 60% load for most of its life may benefit more from optimized no-load loss than from marginal improvements in load loss. Conversely, high-utilization industrial transformers demand aggressive load loss reduction.

6.2 Evaluate Efficiency Classes in Context

Efficiency classes provide useful benchmarks, but they should not be treated as absolute indicators of value.

| Efficiency Focus | Suitable Scenarios |

|---|---|

| Low no-load loss | Light or intermittent load |

| Low load loss | Continuous high load |

| Balanced design | Mixed or uncertain load |

Over-specifying efficiency in the wrong category can increase capital cost without reducing lifetime expense. Optimization means matching efficiency focus to expected operating profile, not chasing the highest efficiency label available.

6.3 Consider the Full Cost Structure

Purchase price is visible and immediate. Loss cost is invisible but persistent.

A practical comparison framework includes:

| Cost Component | Decision Impact |

|---|---|

| Purchase price | Short-term budget |

| Loss cost | Long-term operating expense |

| Maintenance | Reliability and downtime |

| Risk exposure | Price escalation, load uncertainty |

Projects that consider only purchase price often experience higher total cost over time, even when initial savings appear attractive.

7. Case Study: Medium-Voltage Distribution Transformer Selection

To illustrate how lifetime cost optimization works in practice, consider a simplified but realistic project scenario.

7.1 Project Background

- Application: Industrial distribution substation

- Voltage level: Medium voltage

- Expected service life: 25 years

- Load profile: Stable industrial process load

- Electricity tariff: Medium–high, with escalation risk

Three transformer options are shortlisted from qualified manufacturers.

7.2 Technical and Economic Comparison

| Article | Option A | Option B | Option C |

|---|---|---|---|

| Purchase price | Lowest | Medium | Highest |

| Perte de chargement | Medium | Low | Very low |

| Perte de chargement | High | Medium | Low |

| Efficiency focus | Cost-driven | Balanced | Loss-optimized |

| Expected lifetime loss cost | Highest | Medium | Lowest |

Although Option C has the highest initial price, its significantly lower losses result in the lowest lifetime operating cost. Over the service life, the premium paid upfront is recovered through reduced energy loss and lower exposure to electricity price increases.

7.3 Decision Outcome

After evaluating lifetime cost and risk, the project team selects Option B, not Option C.

Why?

- Option C offers marginal additional savings at disproportionately higher capital cost

- Option B provides the best balance between investment and risk reduction

- Load growth uncertainty favors a flexible, balanced design

This outcome highlights an important principle: the lowest lifetime cost option is not always the most expensive or the most efficient one.

8. Common Mistakes in Transformer Lifetime Cost Evaluation

Even experienced project teams fall into predictable traps. Avoiding these mistakes often yields greater cost savings than marginal design optimization.

8.1 Treating Losses as Fixed Numbers

Loss values are often taken directly from datasheets without questioning test conditions, reference temperature, or load assumptions.

Losses should always be interpreted in context, not as isolated values.

8.2 Ignoring Load Uncertainty

Many projects assume a single load factor for the entire service life. In reality, load evolves.

Failing to account for future load growth can reverse the economic ranking of transformer options.

8.3 Mixing Standards Inconsistently

Combining IEC loss data with IEEE-style economic evaluation without alignment leads to distorted results.

Standards should guide—not confuse—decision-making.

8.4 Overweighting Initial Price

Short-term budget pressure often leads to long-term cost exposure.

Projects that prioritize lowest price over lowest risk typically experience higher operational expense and earlier replacement cycles.

9. Practical Decision Checklist for Procurement Teams

The following checklist summarizes best practices for transformer lifetime cost optimization and can be directly applied during technical evaluation and tender review.

Transformer Lifetime Cost Evaluation Checklist

| Step | Key Question |

|---|---|

| Load profile defined | Is the real operating load clearly identified? |

| Electricity price assumed | Are tariff and escalation considered? |

| Loss data standardized | Are all bids based on the same loss definitions? |

| Lifetime cost evaluated | Is loss cost included alongside purchase price? |

| Risk assessed | Are uncertainty and future changes considered? |

Using this checklist ensures that procurement decisions remain technically sound, economically rational, and defensible over time.

Final Thoughts: From Cost Comparison to Risk Management

Transformer lifetime cost evaluation is not merely an accounting exercise. It is a risk management tool.

By understanding how losses, load behavior, and energy price interact over decades, project teams make decisions that remain valid long after construction is completed and initial budgets are forgotten.

The most successful transformer selections are those that align engineering reality with economic foresight.